Dad volunteered for the marines when he was 17, but he had to wait until he turned 18 before he could actually enter. In order to train for the corps, he worked at improving his running abilities. They lived out in the country and their mailbox was about 1/2 mile away from their house. So each day, he would run to get the mail. He got better at it gradually, and before long he would run non-stop, both directions, to and from the mailbox.

He had a job collecting money for the Houston Chronicle. He would borrow his Dad’s truck each Sunday. It had a cracked block, so the radiator did not hold water, and he took plenty with him for his route. He would fill it with water, then go as far as he could, trying to reach hilltops before he could go no further. At the top of a hill, he would turn off the key and coast down as far as he could. He would look for water in gullies first, before he would use the precious water he had stored. Then he would fill the radiator again, drive as far as he could, to the next hilltop, cut the key and coast, then fill it with water again,… This was how he made his 200 mile round trip route each week.

In his spare time, as always, he did a lot of running, hunting, killing and skinning of hides, and curing them for selling. He was always a tough, strong, and very physically fit kid.

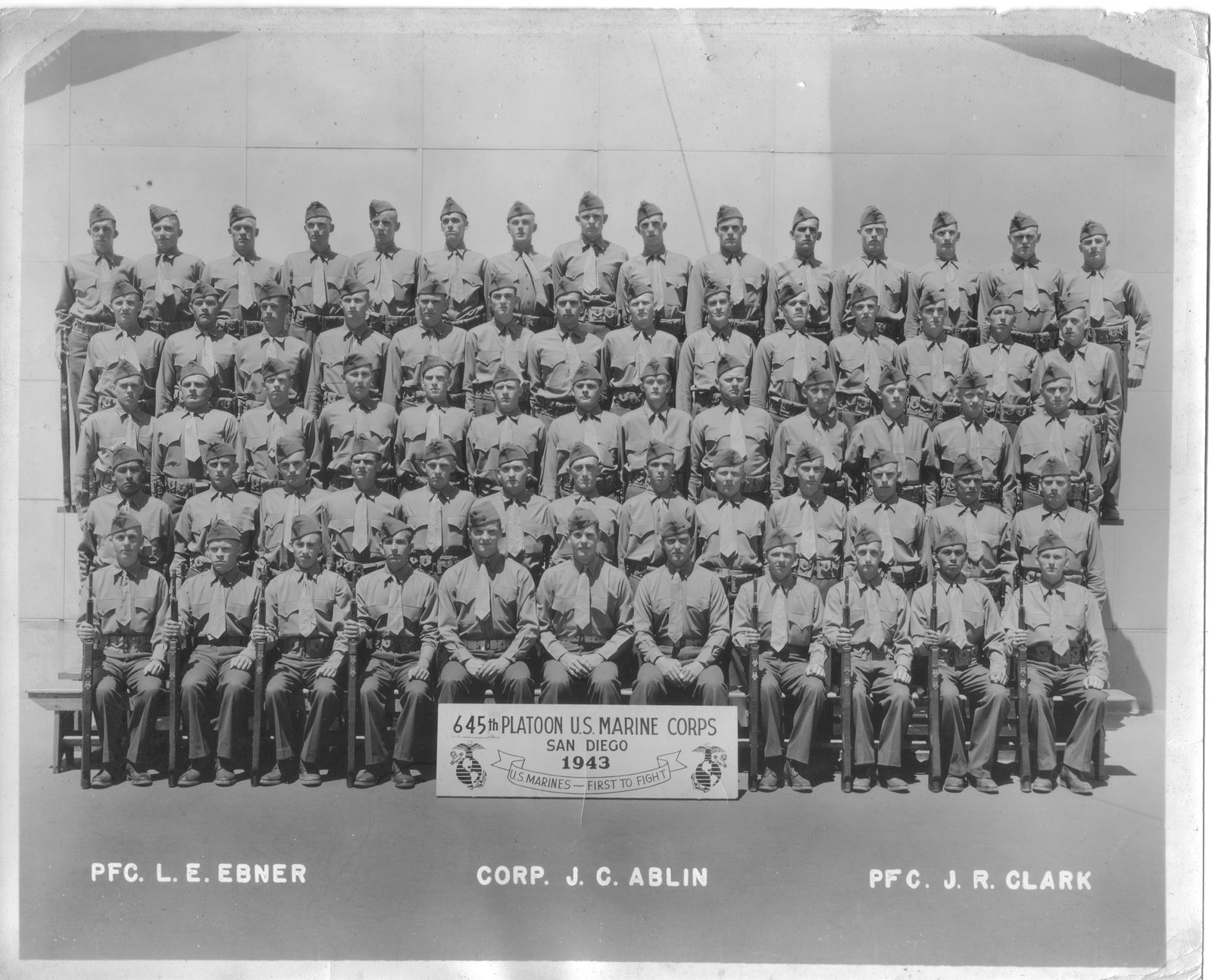

When his 18th birthday arrived, he completed his paperwork at the local recruiter office, then got on the bus and went out to San Diego, California. There were many, many men there, ready for training, and they were divided into groups. He settled into his group of about 75 men, for boot camp.

Each group had a Sergeant, who was “one tough cookie”. His job was to turn smart-alecky civilians, into marines. No kind of smart mouth was tolerated, and you had to stay clean and follow orders. The sergeant would try to make you mad! Calisthenics, wash your clothes, get in order, stay at attention,… He would conduct tedious inspections, turning up his nose and contorting his face to your perfectly clean clothes. Then he might pull off your shirt, drop it on the ground and stomp on it, make you do it over. And they would be as clean as could be.

Occasionally, someone would take him on and there would be a fist fight. The sergeant would beat them up and that would be that. He wanted orderly, obedient people. Sometimes he would have them dress in their best dress blues, shoes shined and buttons polished. Then he would take them out to the beach and make them run in the deep sand, until they fell down.

Dad was among the best runners. The Navajo Indian tribe had a lot of marines. The Japanese could not understand their language. So they often carried radios. A movie was made about them. They are known for their ability to run, as well. 2 of them challenged Dad to a run. None of the 3 of them could ever beat each other. They were neck and neck, all the way.

Dad was assigned to morse code training. “dit – dot – dit – dot – dit – dot – dot – dot”. The goal was to send at 40 words per minute with no mistakes. Write it down, code names in place of dots, send. The training lasted about 6 weeks, and it was hard. He was also trained in semi-fore, which was sending coded messages with the use of flags.

After communications training, he went to the rifle range and made sharp shooter. He had a boil on his cheek during that training, right where the rifle touched his face. But he still shot with great accuracy, despite the terrific pain. And he believes they probably recorded his high pain tolerance.

At the end of boot camp, there was a big beer bust celebration. They had completed boot camp, they were now marines, but not yet assigned. Dad was sitting among friends. Everyone had been drinking. Dad never liked alcohol, but he had been drinking too. There was a message repeating over the loud-speaker, calling for someone sounding like, “Private Lu-Kay”. They probably called for him about 50 times. After quite a long while, someone told Dad that he thought they might be saying his name. So Dad went up and checked things out. It was a Louisiana Cajun, and he said, “I have your billfold”.

The best day of boot camp, was the last day. They had been treated like “dogs in dog prison” for weeks. But the closer time came for them to re-enter civilization, things got some better. Typical early morning drills included calisthenics in cadence with their rifles, while being yelled at by the sergeant. On graduation morning, things were a little different. They were told to put on their dress blues with polished buttons and shined shoes. They all met, all 500 to 1000 of them, on a large parade ground area, where they assembled in rows. They were ordered to attention. Over the loudspeaker, emerged a favorite song of that era, a waltz called, “3 O’Clock in the Morning”. They performed their morning drills to the accompaniment of that song. Dad said it was the most pleasant boot camp experience that he remembers. He had grown up on hillbilly music, guitar and fiddle. At that moment, he lost his taste in hillbilly music, and it has never been the same, since. The song really made an impression on him. It sounded so pretty, and they were like a bunch of New York girls on stage 🙂 This was their graduation ceremony.

| Three O’clock In The Morning Three O’clock In The Morning, performed by Paul Whiteman and his Orchestra for Victor Records. |

After boot camp, they were rewarded with a 10 day furlough. That was enough time to go home. So they sent him there via train.

After having been home several days, and having visited with everyone, he only had 3 hours left, so he decided to go visit his girlfriend one last time. He took his Dad’s truck to her parent’s home five miles out in the country. On the way there, a bridge was washed out. He did not see it, and went right into the creek bed. With a little bit scrambled brains, and an hour to spare before time to board his train back to California, he turned back on foot, and went to a farm house. The farmer came out with his gun, but soon realized that Dad needed help. So he drove him to the train. Dad called his parents to let them know where the truck was. With 5 minutes to spare, he boarded the train. He did not get to see his girl. She sent him a Dear John letter, and married someone else.

Three O’ Clock in the Morning sheet music cover (1921).

“Three O’Clock in the Morning” is a waltz composed by Julián Robledo that was extremely popular in the 1920’s. Robledo published the music as a piano solo in 1919, and two years later Dorothy Terriss wrote the lyrics. Paul Whiteman’s instrumental recording in 1922 became one of the first 20 recordings in history to sell over 1 million copies.

History

Julián Robledo, an Argentine composer born in Spain, published the music for “Three O’Clock in the Morning” in New Orleans in 1919. In 1920 the song was also published in England and Germany, and lyrics were added in 1921 by Dorothy Terriss (the pen name of Theodora Morse). The song opens with chimes playing Westminster Quarters followed by three strikes of the chimes to indicate three o’clock. The lyrics then begin: It’s three o’clock in the morning, we’ve danced the whole night through.

This “Waltz Song with Chimes” created a sensation when it was performed in the final scene of the Greenwich Village Follies of 1921. In this performance Richard Bold and Rosalind Fuller sang the song while ballet dancers Margaret Petit and Valodia Vestoff rang the chimes. Frank Crumit recorded the song for Columbia Records in 1921, but its biggest success came in 1922 when Paul Whiteman released a recording on the Victor label, selling over 3.5 million copies of the record, and fueling the sale of over 1 million copies of the sheet music.

The song has been recorded by some of the most renowned orchestras of the 20th century, including Frank De Vol and his Orchestra (1950), Guy Lombardo and his Royal Canadians (1960), Mitch Miller and the Gang (1960), Bert Kaempfert and his Orchestra (1964), and Living Strings (1971).[6] The song also has become a jazz standard with notable recordings by Dizzy Gillespie (1953), Oscar Peterson (1956), and Thelonious Monk (1969).

The song was also repatriated to the home country of the composer, Argentina, where it was published as “Las Tres de la Mañana” by G. Ricordi & C. and interpreted as a tango vals by the orchestra of Enrique Rodriguez in 1946. (Wikipedia)